Europe has given microplastics on sports pitches the red card. The European Commission (EC) has proposed a ban on microplastic infill on sports pitches with a 6-year transition period to allow people to switch to less harmful alternatives.1 After one and a half years of delay, the EU Commission and member states are one step closer to restricting the supply and sale of products containing intentionally-added microplastics (including those on sports pitches). Scotland and the UK must now follow suit to prevent our environment from being a dumping ground for old car tyres and rubber crumb plastics.

The problem with pitches

Artificial sports pitches have been around since the 1970s, and the number of full-size pitches in Europe has grown threefold between 2006-2012,2 and this has continued to increase in recent years.

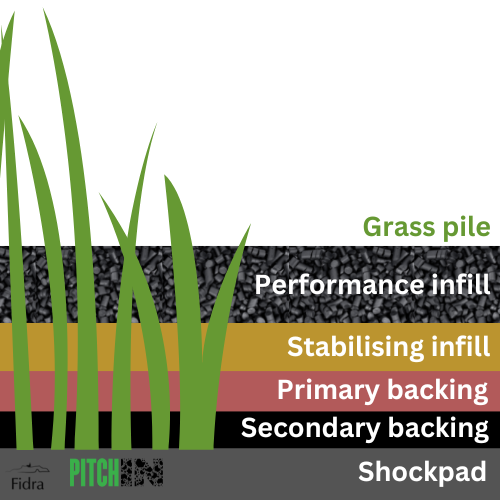

Many don’t realise that these pitches can be a significant source of microplastic pollution; a field study in the Netherlands for example found up to 70kg of rubber granules entering nearby water courses from a single pitch each year.3 Many artificial sports pitches use third-generation (3G) technology. Fine granules, usually made of rubber plastics, are added as a performance infill to create a more comfortable playing surface mimicking real grass. These loose granules sit in-between the strands of ‘grass’ filaments on the top of the carpet (which are also made of plastic and can come loose).

The most common performance infill is made of a synthetic rubber called Styrene Butadiene rubber (SBR). ‘Rubber crumb’ is used on the majority of pitches and is produced by grinding up old vehicle tyres. It is estimated that roughly 51,000 football pitches in Europe are covered with synthetic turf, and 90-95% of these are infilled with rubber crumb.4

Across Europe, between 18,000 and 72,000 tonnes of granulate escape from artificial grass pitches annually.5 Microplastics are washed away with rainwater, cling to the player’s kit and can be displaced from pitches during maintenance activities.

Once in the environment, the microplastics can build up in the local environment and end up in waterways causing harm locally and further afield. For example, SBR has been found in the stomachs of fish, has been found to impact earthworm and plant growth, and can leach harmful substances like zinc.6

The ban

Back in August 2022, the European Commission released its draft proposal, which opted to ban microplastics used as granular infill in sport pitches with a 6-year transition period, in line with Fidra’s asks. This ban was originally suggested by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) in 2020 after which its two scientific committees gave an opinion to inform the Commission’s final decision.

This proposal has been discussed during a meeting with EU Member States on 23 September (REACH Committee); we now await the outcome of their discussion.

The main reason cited for the Commission’s decision to ban the infill was that the material is the largest source of environmental and microplastic emissions of intentionally-present synthetic polymer microparticles at the European level.

The proposal also highlighted that although it would be cheaper to mandate mitigation measures to reduce infill loss, such efforts would still accumulatively, result in large amounts of microplastic being lost to and polluting the environment. Therefore, a ban would be more effective than mitigation measures.

Next steps

EU member states must now vote to approve the regulation. If the majority are in favour of a ban, there will be a proposed six-year transitional period where new synthetic sports surfaces placed on the market must have alternate, less harmful, granular infill materials. When Fidra started work on this issue many years ago alongside our project partners KIMO for our ‘Pitch In’ project, we explored the alternatives to microplastic infill. Natural grass and other organic materials like cork, olive stone and walnut shells have proven to be durable, sustainable, and a suitable alternative to microplastic infill7. You can find information on our alternative infill case study here. Manufacturers of 3G pitches should be made aware of the benefits of alternate, non-plastic, infill materials, and we will continue to promote these materials in line with our Cleaner Pitch Guidelines.

We ask that Scottish and UK Governments take action and follow the EC’s intention to improve the environmental footprint of 3G pitches and safeguard the UK’s environment from hazardous microplastic infill. As they say, goals win games, but so too does forward-thinking legislation!

Visit our website to learn more about our Pitch In project. If you agree that our governments should ban microplastic infill you could also consider writing to your MP to support our call.

[1] https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/comitology-register/screen/documents/083921/1/consult?lang=en

[2] Eunomia Research & Consulting (2018) Investigating options for reducing releases in the aquatic environment emitted by (but not intentionally added in) products. Report for DG Environment of the European Commission p. 169

[3] Weijer, A., J. Knol, and U. Hofstra, 2017, Verspreiding van infill en indicatieve massabalans. Rapport i.o.v. BSCN i.s.m. gemeenten Rotterdam, Utrecht, Amsterdam en Den Haag, I. SWECO, 48 pages.

4] Eunomia (2018) p23

[5] Eunomia (2018) p25

[6] Verschoor, A. (2015) Leaching of zinc from rubber infill on artificial turf (football pitches), RIVM report 601774001/2007

[7] https://www.fidra.org.uk/artificial-pitches/plastic-pitches/solutions/